Introduction

When discussing the history of slavery in the United States, The Church of Latter-day Saints is not a religious denomination that typically comes to mind. Mormons enslaved a small number of African Americans compared to other slaveholding groups in the southern and eastern United States. While the Church did not directly take part in the cruelest forms of chattel slavery, there was no shortage of racial segregation, mistreatment, and denial of basic rights though. The narrative stories of enslaved persons in the Mormon faith offer a view of different types of slavery that existed in the United States, especially between 1830-1860. Some Mormons did whip and abuse enslaved people, but Mormonism also offered many of those enslaved unique opportunities to express their disdain for the institution of slavery with some freedom and little repercussion. These freedoms resulted from the Church’s shifting position regarding slavery as they moved from Illinois to Utah. Narratives of former enslaved people like Elijah Abel, Green Flake, and Jane Elizabeth Manning James, show a multifaceted history of Mormons and their treatment of enslaved African Americans. The early Mormon church often afforded much more liberty and freedom to enslaved people than most other slaveholders, but psychological torment and degradation of character was still extant. They often treated black Mormons as close members of the Church while simultaneously being denied some of the rights and privileges of white members.

The LDS began by taking a purely biblical position on slavery in the United States, which tended to be non interventionist. In Genesis Chapter 4, Mormons find their first argument regarding slavery. According to the King James Version of the Bible, Eve gave birth to two sons, Cain and Abel. Both brothers made offerings to the Lord; Abel sacrificed sheep, and Cain presented fruit from the ground. Cain failed to please the Lord with his sacrifice, and in anger killed his brother Abel. Because of this, God punished Cain with a mark saying, “lest any finding him should kill him.” Some Protestant circles have intertwined this belief with the biblical “Curse of Ham”, where Noah cursed his son to be a “servant of servants.” Other religious denominations repeatedly used this story, like Southern Baptists and Methodists, to support slavery throughout the 1800s. The firmly held belief that the “mark of Cain” referred to black skin was commonplace among the Mormon church. In the Book of Mormon, Joseph Smith’s first written scripture states, “It is against the law of our brethren…that there be any slaves among them; therefore let us go down and rely upon the mercies of our brethren.” Joseph Smith later laments, while translating the Bible into the Mormon Book of Moses, that the “seed of Cain were black.” This is in fact the only passage in the Book of Mormon that contains a direct reference to the color of skin being equated with the mark of Cain. Some perceived a few of his writings as pro-slavery and the subsequent interpretations of this passage became the foundation for the support of legalized enslavement in the Church of Latter-day Saints. There are no other biblical references in the Book of Mormon or in the Pearl of Great Price, which contained some Old Testament books reinterpreted by Joseph Smith for the Mormon Church. Smith’s contradictory writings, some anti-slavery, make it difficult to understand how the LDS Church would devolve into support of slavery after the death of Joseph Smith.

Smith was no doubt aware of the social and political crisis that slavery created. The fear of black slaves revolting, like the Nat Turner Rebellion in August 1831, caused a stir to action among slaveholders increased intervention by abolitionists. By 1832, Mormons had two headquarters: one was in Kirtland, Ohio, and the other in Jackson County, Missouri. The Mormon population had become increasingly concerned with the ramifications of slavery, specifically the toll it had taken on those seeking salvation from God. On July 20, 1833, leaders of the Jackson County Mormons were expelled from the state after publishing an anti-slavery article in a Mormon periodical, The Evening and Morning Star. The writer of the paper, a prominent Mormon named William W. Phelps, wrote: “We fear, lest, as has been the case, the blacks should rise and spill innocent blood.” Distorting his own views, possibly in an appeal to hold a more moderate stance, Philips stated that Mormons opposed admitting free blacks into their Church.

The statements were conflicting and obscured the stance that Mormons had on slavery. Nevertheless, an angry mob descended on and destroyed the Star’s office. There are other reasons for Joseph Smith discontinuing the support of slavery within the Church. Mainly, that Joseph Smith was running for President of the United States in 1844. After the Missouri Compromise of 1820 changed the political landscape, eventually radicalizing both sides to eminent action, Smith made the statement “we are the friends of equal right and privileges to all men.” With this proclamation, Joseph Smith placed himself among the abolitionists, but they have misinterpreted his words. Given the hostility against the Mormon population, it is more likely that Smith was preaching for equal treatment under the law for the Mormon population. He made no direct statements about slavery until 1844, during his bid for the Presidency. Smith declared that abolitionist violence and the abuse of slaves could no longer continue in the United States. He claimed the effects of events like “Bleeding Kansas”, “Harper’s Ferry”, and a fear of an impending Civil War influenced him in this proclamation. Smith did not commit to abolitionist tactics, but both he and the Mormon Church, through his leadership, called for a gradual emancipation of slaves.

Smith’s election bid would inevitably end in his assassination after an anti-Mormon mob overtook the jail where he and his brother Hyrum were being held for treason. Brigham Young was a prominent leader of the LDS Church and one of Joseph Smith’s Twelve Apostles. After Smith’s death, he declared himself President of the Church of Latter-day Saints. He did this in a feisty exchange with other Church leaders, the Twelve Apostles. Young was a prominent leader of the LDS Church and one of Joseph Smith’s Twelve Apostles. After Smith’s death, he declared himself President of the Church of Latter-day Saints. One of the Apostles of the Church, Orson Pratt, told Young that they served the institution like the House of Representatives in the United States and that by implication, Young was the Speaker of the House. His reply to the Twelve Apostles of the Church was a fiery, “Shit on Congress!” Brigham Young took charge of the bulk of the Church and began integrating Southern slaveholders into their ranks. Joseph Smith’s grandson, Joseph Smith III, led a group of moderate Mormons who distanced themselves from Young’s radical ideas. The growing anti-Mormonism sentiment in the United States contributed to some key tenants of the faith undergoing drastic changes. Young found that slavery and the support of Southern Mormons was necessary to increase Mormon numbers after taking control of most of the Church of Latter-day Saints.

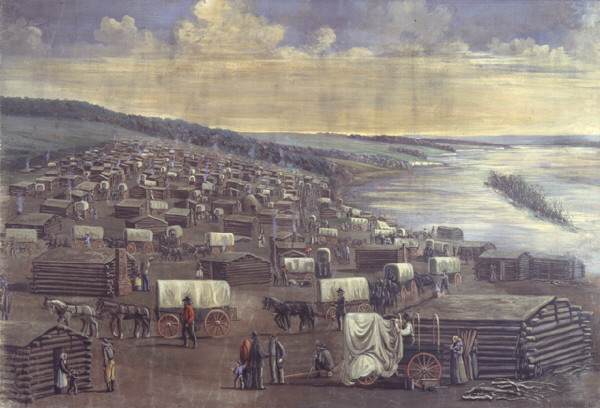

The primary reason for the split in ideology was deeply entrenched in different notions of how to increase Mormon safety. Joseph Smith III believed that assimilation was necessary to ensure safety and prosperity for the Mormon believers. Brigham Young viewed his followers of the Church of Latter-day Saints as a people set apart from the rest of Western civilization. This was certainly not a novel approach, as we can trace the concept of mass migration from persecution back to the Jewish followers of Moses in the Exodus story of the Old Testament. As the Exodus story has intertwined itself with people who have become systematically oppressed and abused, it is unsurprising that the bulk of the members of the LDS would side with Brigham Young. These followers would participate in their own Exodus, following him to one of the far edges of the United States in 1847, the Utah Territory.

As the Church fractured, followers depended on the surrounding culture when analyzing their beliefs on slavery. If the state they resided in was a free state, most Mormons considered themselves to be abolitionists. After the death of Joseph Smith, the LDS split into two primary factions. Those who followed Brigham Young to the Utah Territory had not yet decided their position on slavery in the United States. Because of this, Young began instituting slavery and allowing the transportation of owned slaves into the Utah Territory. The other faction, controlled by Joseph Smith III, eventually became known as the Community of Christ. They held close ties to Republicans in Illinois and espoused abolitionist ideas.

Once Mormons under Brigham Young’s leadership rested in the Utah territory, most initially ignored the practice of slavery. A large group of Mississippi Mormons brought as many as 87 slaves with them to Utah. In a search of census records, it is probable that these may have been some of the only black slaves in the Utah territory. Despite the existence of theses slave communities, Mormon leaders denied the existence of slaves in their territory, most notably to Congress following the Missouri Compromise of 1850. When Congress tried to assimilate the Mormon population in Utah back into the United States through statehood, they no doubt remembered the antislavery stance of Joseph Smith. Brigham Young, echoing some ideas about mistreatment of slaves, but also condoning it in 1855, wrote, “The blacks should be used like servants, and not like brutes, but they must serve.” The Utah legislators being asked to decide the fate of slavery in the new state were a new type of Mormon. Their new direction under the leadership of Brigham Young would become a point of contentious debate in the United States for decades to come.

Those living in the eastern United States often held Mormons as disruptive of a free and Christian society. This was especially true of those who read weekly about the events unfolding in Utah. An article titled “Mormonism versus the Nation” in the Christian Advocate declared bluntly, “The Mormon hierarchy and public security can by no device be joined together. It means freedom or slavery in its worst form.” The same article also reveals Christian sentiment about Mormonism in relation to political affairs, concluding that the religion would prove destructive to the State itself. This perceived incompatibility of Mormonism and the United States legal system became known as “the Mormon question”. Although these issues with Mormons may have exaggerated and sensationalized local issues, rather than national, as most problems never reached the level of the Supreme Court or U.S. Congress. When Mormons came into a town, the surrounding citizens often met them with hostility, like the fate of Joseph Smith. The reason for this aggressive behavior was a combination of Mormons stance on polygamy and slavery. Mormons were not the only group who saw the LDS Church’s move to Utah as an Exodus story. The New York Evangelist wrote, “If their so-called spiritual rulers, like King Pharaoh, will not let them go, a pressure like the plagues of Egypt must be brought to bear upon them.” The US government was of a similar mind when discussing Mormon control in the state of Utah. In 1857, Brigham Young, now Governor of Utah, asked the U.S. government for $40,000 to build infrastructure in the state. They denied the bill on the House floor, with many congressional representatives agreeing that Mormons in Utah did not live in decency and disregarded the laws of the United States. At this time, Utah Mormons still practiced polygamy and slavery, despite the former being outlawed in many states. An official end to the practice of polygamy by the LDS would not happen until 1890. In relation to slavery, The LDS Church had conducted Lamanite missions since the 1830s. These missions sought to convert Native Americans to Mormonism, seeing them as one of the lost tribes of Israel. Native American outreach was normal for the Mormon Church in the 1850s, but the enslavement of Native Americans being fully condoned by the Church was another matter.

Native American Enslavement in Utah

Slavery was not a new concept in the Utah Territory. Dating back to the thirteenth century, long before the Mormons arrived in the Salt Lake area, the Great Basin of Utah served as a market for Native American slaves. Spanish and Mexican residents sold captive Native Americans that the Paiutes and Utes had kidnapped from rival tribes. These “pre-contact” Native Americans even sold slaves to each other for foods or goods before the arrival of the Spanish. It is therefore difficult to place all blame on the Mormons for the opening trading of human beings in the Utah territory. It is a better assessment to say that Mormons first attempted to convert or “civilize” Native Americans in the region. When this goal ultimately failed, Mormon citizens took their cues from the surrounding culture for ideas on how to proceed. Mormons would often use the term, “buying the slaves into freedom” to justify Native American enslavement. Tensions between the Utes and Mormon settlers intensified. Eventually, Young declared war on the Utes Tribes saying, “We shall have no peace until their men are killed off. Let it be peace with them or extermination.” Between 1849 and 1851, these conflicts resulted in the death of almost sixty Utes men, women, and children. The Church of Latter-day Saints desperately began a baptism campaign, seeking to convert as many Native Americans as possible. After nearly five months of the conversion campaign, Young resorted back to violence against the Utes tribes. He claimed that the Utes tribes were incapable of assimilation because they preferred idleness and theft to plowing and sowing. As the Missouri Compromise of 1850 gave the citizens of Utah the ability to determine the fate of the territory and their position on the legality of slavery, Brigham Young then capitalized on enslaving large populations of Paiute Native Americans.

The United States government met the Utes, who became problematic for the Mormon Church, with an Indian removal plan. The Indian removal, hinging on placing Native Americans on specified reservations, closely echoed the United States 1830 Removal Act. This legislation forcibly removed the Five Tribes that occupied areas in the Northeastern and Mid-west of the United States, relocating and restricting them to specified reservation lands set up by the US government. This may have contributed to the reasoning that what befell the Paiute tribes in Utah went unchecked by the United States government. If the LDS Church was acting in the same manner as the United States in relation to the Utes tribes, why would they treat the Paiutes any differently? The Church began trading Native American slaves in the Utah Territory and passed several legislative measures in the state. In 1852, a Mormon controlled Utah Territorial legislative body passed An Act in Relation to Service. The act legalized slavery in Utah and required that slave owners punish and reprimand their slaves for any wrongdoing. In addition, and potentially more worrisome to those living in the eastern United States, it mandated that slaveholders retain slaves for a period of no less than 20 years. This was much longer than the nearby states of California and New Mexico. Mormons in the Utah Territory began aggressively trading Native American slaves among Native tribes in the region. They established multiple subsequent acts of legislation to differentiate blacks from Native American slaves and create a separation between the different tribes. With one of these, An Act for the Further Relief of Indian Slaves and Prisoners in 1852, the Mormon controlled state of Utah expressed it was “the duty of all humane and Christian people to extend unto this degraded and downtrodden race such relief as can be awarded to them.” Mormon legislature merely justified slavery by suggesting that placing them in bondage was improving their current condition. This did not differ from the shift in southern states from slavery to “apprenticeship”, whereby former slave owners would continue to indenture individuals after the Civil War.

The Mormon Church implemented four institutions in 1850 to “civilize” the Native Americans in Utah: adoption/indenture, Lamanite Missions (like those in the 1830s), intermarriage promotion, and Indian farms. The dramatic shift from these outreach policies occurred in 1851 after only a year of failure, when Brigham Young instructed Mormons to buy as many Lamanite children as they could in order to convert them from within their homes. Young’s initial rational was that it was more appropriate to feed Native Americans than fight them. Many historians have taken issue with his stance, saying that Utah’s indenture laws “created a system of Indian slavery, as white Americans used the law’s provisions to actively seek women and children to steal.” Shortly after the Civil War ended, Congress ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, and the United States government turned their attention to Utah. In 1866, Congress passed a federal law against kidnapping people with the intention of selling or indenturing them. This ended the barbaric form of Native American slave trade in the western states.

While they withdrew the process of forced enslavement and abuse, the practice of indentured servitude or adoption continued well into the 20th century, officially ending in 1986. In the state of Utah, there were no separate schools for indentured Native Americans. This was far different from segregation practices that took place in the rest of the United States as it related to people of color. There were two primary reasons for desegregated schools in Utah. The first was that Mormons saw Native Americans as broken descendants of one of the twelve tribes of Israel. It was therefore the Mormon mission to preach the gospel of the Bible and Book of Mormon in order to assimilate them through education. This assimilation technique closely mirrored the Spanish Catholics during the 17th century rather than the Protestant methods in New England. The second reason for integration was that because of the prevalence of European immigrants who converted to Mormonism. These individuals spoke little English themselves and often resorted to learning Native American languages. This meant that integrated schools made communication more expedient for all parties involved, because Native Americans had difficulty learning the English language. Another issue with indenture laws in Utah involved a proclamation by Brigham Young that encouraged intermarriage between Native Americans and Mormons. Jacob Miller noted that, “President Brigham Young gave us some advice as to trying to get wives from among the Natives. They have refused to let their daughters go or at least seem not willing.” Other accounts from Mormons living in Utah stated that fathers among the Native Americans would often bring them their daughters to marry. I dispute this narrative, as it was clear most Native American tribe males did not welcome intermarriage. Mormons living in Utah today have sought in some ways to reconcile these acts by restoring Native American names to local monuments and landmarks. Some historians argue that this is simply a sign of tension that still exists between Mormons and Native Americans, walking a line between “Indian-as-brother and Indian-as-other.”

As the stance on slavery shifted following the Civil War, Mormons moved from one form of slavery to another. While the early stages of the Church of Latter-day Saints were more reflective of the surrounding society, their desire to continue enslavement or indentured servitude of Native Americans presents a peculiar case regarding the justifications of slavery. While most slave plantation owners in Southern states found the basis for slavery and servitude in the Bible, Mormons struggled with the idea of placing people into a violent form of bondage. The Mormon population that settled in Utah faced unique situations that caused them to reshape their ideas on slavery. Rather than placing Native Americans into slavery that involved long hours and violent retribution, they chose to assimilate with the notion of salvation. Those in the region never intended indentured servitude in the state of Utah as a workforce, but rather a means to civilize a culture. The goal of Native American conversion by Mormons was to restore the last lost tribe of Lamanites back into the House of Israel, a utopian effort to eliminate class and racial differences. Native Americans in some ways prospered in the Utah territory because of this civilization. The schools that Mormons built to teach the Utes and Paiutes in the area increased their chances of surviving in a culture of white European descendants, while also giving them tools with which to raise themselves out of dependence and poverty on the government. Perhaps Native Americans in Utah fared better than other tribes in the United States in term of assimilation and prosperity, but this process came at the cost of losing their culture and way of life, as Utes and Paiutes became disconnected from their language and tribal support systems.

Anti-Slavery Mormons

When Joseph Smith began his campaign for President of the United States, he espoused abolitionist views. As pressure increased on the Mormon community, he later amended these notions to be simultaneously anti-slavery and anti-abolitionist. The first major issues with abolitionist activities occurred in Kirtland, Ohio. An abolitionist organizer named James W. Alvord established a chapter of the American Anti-Slavery Society in Kirtland. Because the Mormons showed little resistance to Alvord, slaveholders and anti-abolitionist groups linked them to the abolitionist movement. While in the slave state of Missouri, Mormons under Smith defended slavery only because of the surrounding sentiments. Any views considered to be abolitionist in nature were met with hostility. Joseph Smith gave a speech on the growing violence between abolitionists and supporters of slavery. In a Christmas Day speech in Kirtland in 1832, he lamented that “numerous wars would come to pass…the Southern States shall be divided against the Northern States.”

Because Mormons in Missouri had enough to contend with regarding their religion, specifically their stance on polygamy, they seemed to keep quiet about their views on enslavement. This is also due in part to the vigorous support of slavery in Missouri during the 1830s. Non-Mormon residents circulated a “Secret Constitution” condemning the anti-slavery views of the Saints in Jackson County, Missouri. Attempting to reduce blowback, the editor of the Mormon paper, Evening and Morning Star, wrote that the Church did not want free blacks in Missouri or in the Mormon Church. Despite these developments and attempts at public outreach, surrounding communities continued to ostracize Mormons in Missouri and Illinois until their departure to Utah in 1847. By all accounts, many Mormons held anti-slavery beliefs while in Missouri, but remaining quiet about their beliefs was merely a necessity to survival. Because of this, blacks in the Mormon Church had a very different outlook on these peculiar and sometimes contradictory stances.

Prior to violent clashes between abolitionists and anti-abolitionists, a few prominent African Americans joined the Mormon Church freely. One was a proselytizer known as “Black Pete”, who the Church baptized in 1830. We know little about the origins of Pete, but one account states he was born to slave parents and migrated from Pennsylvania to Ohio that same year. In 1831, Joseph Smith had a revelation that condemned Black Pete. The story of Pete and his legacy with the Church only lasted for less than a year. They excommunicated him from the Church after requesting to marry a white woman. Black Pete’s experience with the Mormon movement did not extend to others, though. He was somewhat of an anomaly, as Mormons seemed to treat other black converts with a far more embracing standard. Three noteworthy figures in black Mormon history had a long and illustrious relationship with the Church, even to the far outreaches of the western United States.

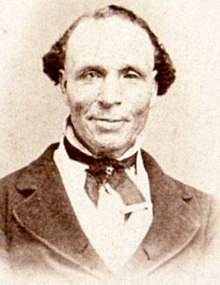

Elijah Abel

His missionary work in Canada was no doubt the result of being manipulated somewhat by the Church. Ontario contained a strong population of African Americans, and Joseph Smith likely sent Abel there to assess the possibility of establishing a black Mormon congregation. No documentation proves that Abel ever established a community in Canada. Because of the Rebellion of 1837 between the British and French, most Mormons fled the region. Despite his lack of education, most Mormon apostles viewed Abel as a brilliant orator. A fellow Mormon proselytizer, Eunice Kinney, recalled that, “the Spirit rested upon him and he preached a most powerful sermon. It was such a Gospel sermon as I had never heard before, and I felt in my heart that he was one of God’s chosen ministers.” Abel also had no qualms in preaching to white men about equality. The laity seemed to accept this sentiment, despite it being challenged by the doctrine of the Mormon Church. This highlights a possible disconnect between the leaders and apostles of the Church and their Mormon followers at large. It is also likely that political discourse and the presentation of Church doctrine to non-Mormons influenced some of the conflicting teachings.

Elijah Abel could preach freely for the Church in areas like New York, without penalty for his anti-slavery views. Abel was also a fundamental piece in the survival of the Church. In June 1841, he helped a group of Mormons rescue Joseph Smith after his capture in Illinois. In return for his help and obedience to the Church, they ordained Abel a “competent Elder” in the city of Cincinnati. The town was comprised of mostly free black laborers, but tensions regarding slavery soon made the area volatile and inhospitable, especially to Mormons. There is no doubt that Joseph Smith knew about the volatility when he sent Elijah Abel there. One could infer that Smith chose Abel for this task because of the color of his skin, although many described Abel as mulatto, or because he believed him to be the proper voice for the Church in the area. His choice to send him on his own to Cincinnati, attests to his potentially revered opinion of the man.

Abel’s preaching in Cincinnati alarmed non-Mormons and may have in some ways contributed to growing resistance to the Church in Ohio. While in Cincinnati, Joseph Smith often praised Abel for riding in his own carriage and preaching to “bind the races together.” Following Joseph and Hyrum Smiths deaths, the Church fragmented. Nowhere was this more visible that in Cincinnati, where the local Mormons declared Abel an apostate. In June 1843, a disciplinary council in the Church instructed Abel that he could only preach to African American populations. It is possible that by restricting Abel to black citizens in Cincinnati, the elders believed it would lessen criticism that Mormons were promoting racial equality. Brigham Young’s control of the Church only made matters worse for Abel and other black Mormon men.

Unlike Joseph Smith, Young had no issues using racial epitaphs when addressing black members of the Church. He reflected the sentiment of a northern journalist Frederick Olmstead in one of his addresses saying, “[I’m] shocked to see that negro women are carrying black and white babies together; black and white faces are constantly thrust together out of the doors, to see the train go by.” After arriving in Utah, Young cemented his views on racial inequality and addressed the elders of the Church, including Elijah Abel. In his address is the first recorded discriminatory Church doctrine related to black members in the priesthood. Wilford Woodruff compiled a history of the meeting in 1852 stating, “Young replied with much clearances that the curse remains upon [blacks] because Cain cut off the lines of Abe to prevent him and his posterity…prohibiting the Priesthood.” When the Mormon view on slavery changed, they stripped him of his priesthood, but he remained in the Church, hidden from the public. Although he was a close member of the Church, the situation in slave states like Missouri and Utah caused Abel to receive continuous discrimination. Abel never abandoned the Church and told the Church’s President, John Taylor, before his death, “[I] hope to be the welding link between the black and white races.” Abel died on Christmas day of 1884 in Salt Lake City, Utah as an ordained member of the Church.

Green Flake

In Utah, Flake was close to two other enslaved men: Hark Lay and Oscar Crosby. All three of the men came from Mississippi plantations, so they likely shared a lot in common with one another. There are claims that someone gave Green Flake as a gift to the Church, and the Church elders subsequently freed him around 1850. Other than Church documents, there is no research to corroborate this story. No other enslaved persons were ever freed by Church leaders who were all pro-slavery at this time. An 1860 state census confirms that Brigham Young freed Green long after this supposed event. It lists Green with his wife Martha and their children, as free residents of the Union. His freedom occurred prior to slavery being outlawed in Utah in 1862. Flake contributed heavily to the establishment of outposts in the west, and his family remained with the church long after his death. His daughter and granddaughters became foundational members of the church in Utah. Green and his son Abe eventually moved to Utah after being freed. Abe became a respected member of the founding population in Gray Lake, Idaho. Abe Flake and Green Flake were among the earliest Mormon settlers who moved to Bonneville County near Idaho Falls in 1899. The Leggroan’s married the children and grandchildren of Green Flake, thus creating a generation of black settlers in Idaho. Clara Stevens Terrell, his daughter, later stated in an interview, “My father was a farmer, and for years we were the only African American family in that area. My father was very well thought of in the community. He and my mother were both born in Utah and my father’s mother was born in Utah. Her father, my grandmother’s father, came West with Brigham Young’s party.” This statement shows a clear reverence for African American members of the Church in Utah and Idaho, but racial segregation and discrimination still plagued the black population in both states. African Americans often had to adhere to curfew laws, and there were extensive employment discrimination laws that kept them in specific jobs. Today, the Brigham Young statue in Salt Lake City lists Green Flake’s name, his slave status absent.

Jane Elizabeth Manning James

It is important to note that James does not make race a central part of her story. Likely, the biographer did this to make her story sympathetic and tolerable to a white Mormon audience. Some researchers say that it is also possible the woman who aided James in writing her autobiography, Elizabeth J.D. Roundy exerted some influence. By the time they wrote her story, James was nearly blind and unable to wield a pen. For this reason, the Church provided her with the aid of a white woman who had close ties to the elders of the Church. Roundy claimed James merely dictated the facts to her, which we have no reason to disbelieve. From the stories told about her, James was clearly a somewhat stubborn and independent woman. In several letters and documents, James references “her people” and constantly prayed for African Americans to convert to Mormonism. Therefore, it is unlikely that Roundy misrepresented James’ beliefs or stories in any significant way.

In Illinois, James lived and worked for the Smiths until Joseph’s death in 1844. In her autobiography she discusses how cordial the Smith family, and most Mormons for that matter, were to her. It is noteworthy that James’ racial status did not seem to restrain her from ascending the ranks of Mormon membership. She rose from Smith family houseguest to live-in servant, eventually becoming a close family confidant and family member. The life of Jane Manning James challenges some preconceived notions about how Mormons viewed slavery. Despite her race and the tumultuous times of slavery and abolition movements, she became a close family member to two of the most prominent households in Mormonism. The Smith and Young family both seemed to have accepted her as one of their own, although with the Young’s she certainly faced more hostile and uncivil behavior from Utah members.

After Smith’s death, James lived with Brigham Young and migrated with the family to Utah. In May 1848, during the journey, she gave birth to her son Silas. Patty Sessions, a Mormon midwife, details the courage and determination of James, both before and after the birth. Sessions simply identified her as “black Jane” in her journal. In her own biography, James referred to her race only a few times. Instead, she hoped readers would identify her as a Mormon pioneer who was one of the first ones to make the perilous thirteen-hundred-mile journey from Nauvoo to the Salt Lake Valley. Later, she gave birth to her daughter, Mary Ann, the first black child born in Utah. James’ story tells us a great deal about life in these central households and how Church elders perceived African-Americans. James requested she receive endowments of her own, claiming her family as an independent part of the Church. They denied her several times, and she never achieved her own blessings by the elders.

James left most of her family behind when she journeyed to the Utah Territory. Her children and husband, Isaac James, were the only ones who accompanied her. They eventually had 8 children together, but Isaac abandoned the family around 1869. He made his way to California and never communicated with the family again. Left with only her children in the Utah territory, Jane James asked the council to seal her to an African American elder of the Church, Walker Lewis. Like Elijah Abel, Lewis was a prominent and important figure of the Mormon Church. Historic records of the Church show that Elijah Abel, Joseph T. Ball, and Walker Lewis were the only three black men who held the priesthood. Systemic racism kept Lewis and James from achieving their wishes, though. The other elders of the Church repeatedly denied their marriage. James was acutely aware of the discriminations she faced. In her letter asking the council to seal her to Lewis, she reminded the elders, “I am coloured.” Unlike the legacy of Flake, James’ children were all expelled from the Church for various reasons. Eventually, the Church granted her requests to be adopted by Joseph Smith’s family lineage. In another blow to James, this came with the stipulation that they would adopt her as a servant, not as a child of the Smith family.

Jane’s experience in the LDS Church was one of exclusion and subordination. She was unable to participate in temple ceremonies and was constantly fearful for her place in the afterlife. Being granted adoption as Smith’s servant meant she would maintain this status after death. At her funeral, the President of the Church said that she had become “a white and beautiful person.” Following her death on April 16, 1908, the Deseret News, a Mormon newspaper, rushed to publish an obituary for her on the front page of its paper.

Conclusion

The prohibition against the full participation of blacks in the Mormon Church went unchallenged for more than a century. While the Church of Latter-day Saints had a peculiar way of dealing with the “peculiar institution”, we must understand that the Church elders were undoubtedly racist in their ideology and treatment toward African Americans. The Church attempted to justify the denial of rights to black members by invoking scripture and God. Other churches in the United States who have had a history of racist teaching and support of slavery have since denounced those teachings and apologized. To this day, the Mormon Church has made no such apology or change in official doctrine. While they have allowed black members of the Church into the priesthood, beginning in 1978, outsiders feel the Church has failed to combat systemic injustices in its teachings. The opening of the priesthood to black Mormons in 1978 resulted in the exodus of nearly 20,000 white members of the Church.

The lives of Elijah Abel, Green Flake, and Jane Elizabeth Manning James highlight a misconception that no prominent black members of the Church of Latter-day Saints ever existed. It also shows us how deeply entrenched the racist ideas of the Church are and why they are so difficult to change. While some religious groups used the Bible to defend their views on slavery and racial segregation, the Mormon Church built the idea of salvation around race. Only those who were “white and pure” can ascend into the kingdom of heaven. Rather than turn away from this belief, some African Americans, for a multitude of reasons, stayed with the Church. Whether they hoped to reform Church ideas from within or they truly believed the teachings were correct, they never abandoned the Mormon faith or directly disobeyed the elders. In the case of Jane James, there is a focus on Joseph Smith and his teachings. It is likely that James does this in order to fight against racial discrimination that Church doctrine had proliferated after Smith’s death. One thing is for certain, we can by no means consider the plight of African American enslaved persons in the Church of Latter-day Saints during the mid-19th century to be typical.

Bibliography

Bringhurst, Newell G., and Darron T. Smith. Black and Mormon. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2010.

The Evening and the Morning Star Extra (Independence, MO). “Free People of Color.” July 16, 1833. https://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/digital/collection/NCMP1820-1846/id/5850.

Harris, Matthew L. “Mormons and Lineage: The Complicated History of Blacks and Patriarchal Blessings, 1830–2018.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 51, no. 3 (Fall 2018), 83. http://search.proquest.com/docview/2161264295/.

Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate (Kirtland, OH). “Address.” October 1834. https://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/digital/collection/NCMP1820-1846/id/7160/.

Mueller, Max P. “From Gentile to Israelite.” In Race and the Making of the Mormon People. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2017. doi:10.5149/northcarolina/9781469636160.001.0001.

Newell, Quincy D. “The Autobiography and Interview of Jane Elizabeth Manning James.” Journal of Africana Religions 1, no. 2 (2013), 251-291. doi:10.5325/jafrireli.1.2.0251.

“News and Views: Blacks at Brigham Young University; Objects of Curiosity But No Longer a Breed Apart.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 43 (November/December 1995), 22. http://search.proquest.com/docview/195555714/.

Oliver, Mamie O. “Idaho Ebony: The African American Presence in Idaho State History.” The Journal of African American History 91, no. 1 (2006), 41-54. doi:10.1086/jaahv91n1p41.

Ricks, Nathanial R. “A Peculiar Place for the Peculiar Institution: Slavery and Sovereignty in Early Territorial Utah.” Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2007.

Smith, Joseph. The Book of Mormon: An Account Written by the Hand of Mormon Upon Plates Taken from the Plates of Nephi. Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1849.

Smith, Joseph. The Doctrine and Covenants of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Carlisle: Applewood Books, 2009.

Stevenson, Russell W. “A Negro Preacher’: The Worlds of Elijah Ables.” Journal of Mormon History 39, no. 2 (April 2013), 165-254. http://www.jstor.org.mutex.gmu.edu/stable/24243899.

Stevenson, Russell W. “More on Elijah Ables.” Journal of Mormon History 39, no. 4 (October 2013), vi-x. https://www-jstor-org.mutex.gmu.edu/stable/24243822.

Times and Seasons, Vol. III, no. 15 (Nauvoo, IL). “The Mormons.” June 1, 1842. https://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/digital/collection/NCMP1820-1846/id/9862.

Weathersby, Ronald. “Black Mormons say History of African Americans and their Church is Misunderstood.” The Tennessee Tribune (Nashville, TN), November 24, 2011, 1A, 8B. https://search-proquest-com.mutex.gmu.edu/docview/910933105.

Wolfinger, Henry J. “MSS SC 1069; A test of faith: Jane Elizabeth James and the origins of the Utah black community; 20th Century Western and Mormon Manuscripts; L. Tom Perry Special Collections.” Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, https://findingaid.lib.byu.edu/viewItem/MSS%20SC%201069.